More than eight years into the Ivorian conflict and on the eve of the presidential elections which are meant to signal the end of violence, Abidjan’s former militias are still very much a tangible presence in the southern part of the country. Beyond occassionaly voicing their discontent over the unsettled 1000-dollar demobilisation fee, ex-militia members are active in ways that were difficult to predict when they first emerged in the early days of the conflict. In view of the upcoming elect ions it is important to assess the militias’ involvement in politics and vice-versa.’Guantánamo’, the last remaining barracks of the GPP militia, is the place from where some of these developments can be observed.

‘Self-defence groups’ (‘Groupes d’autodéfense’) is the name the militias prefer for themselves because it stresses both their professed non-offensive stance and the protective nature of their mission with respect to their’own’, local or national community – however exclusive that may be at times. The militarist groups came into being soon after the insurgency of September 2002, backing the besieged president Laurent Gbagbo and supporting the army that had remained loyal to him. Appeals by youth leaders such as Blé Goudé and Eugène Dué resulted in the mobilisation of thousands of youngsters. About 3000 were conscripted into the loyalist army while more than double that amount worked its way into informal military structures patronized by members of the armed forces, the state administration as well as politicians. Many fought on the front line, situated along the demarcation line that divided the loyalist south from the rebel-held northern part of the country. After January 2003 most of the fighting was over, but many militia-members remained stationed on the front and were involved in occasional outbreaks of violence until the loyalist offensive operation’Dignity’ in November 2004 failed, and with it the prospect of a military solution to the conflict.

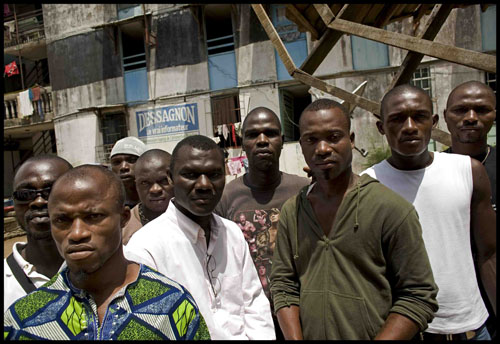

The slow and arduous peace process that followed saw the immediate demobilisation of many militia members and the redeployment of the remaining factions to the economic capital Abidjan. For many years Abidjan witnessed the setting up of barracks mostly by its largest and most renowned militia grouping, the GPP (Grouping of Patriots for Peace). One after the other the camps were cleared by the army until, since the fall of 2008, the camp at Yopougon was the only remaining. It is a vast desolate site at the entrance of Abidjan’s largest commune and comprises two unfinished buildings. An estimated forty families of ex-GPP members have found refuge in two monumental concrete shells, the largest and most populated of the two is called’Guantánamo’.

Rather than referring to the American detention centre on Cuba or to a jail in general, residents at Guantánamo maintain that for them’Guantánamo’ means’fortress, a place where one feels secure’. The tags, graffiti and full colour wall paintings, the makeshift doors or pieces of cloth that close off the families’ bedrooms, the telephone numbers and biblical quotations inscribed on the weather-beaten walls, all give Guantánamo a sense of home. As the only remaining camp it has become as much a symbol of the militia’s resilience as of its need for security and belonging in a long history of political exploitation and lack of recognition.

After the militia redeployed to Abidjan, its main activities were propagandist in nature. Most spectacular of all were their drill marches through the streets of the city, aimed at boosting the morale of the loyalists and intimidating rebel sympathizers who constitute a substantial part of the Abidjanese population. The militias also saw themselves as occupying certain’intelligence’ or vigilante roles in trying to identify rebel supporters who were scheming against the Gbagbo regime. The militias increasingly came to be seen as spoilers of the peace process, and were abandoned by politicians and apparatchiks alike. At the same time its members saw their chances of vertical networking (with highly placed patrons) and social mobility (e.g. joining the army) evaporating.

As an alternative, the majority of former militia members follow the short professional training programmes that form part of the national demobilisation and reintegration schemes, and seek opportunities in administration, the trades and manual labour. Others – a small but interesting group- have ventured into artisanal and artistic areas such as the visual arts, literature or music. Others are less inclined to make a clean break with the past, opting instead to make good use of the skills acquired in the course of the eight-year conflict: handling weapons, a few guerrilla and intelligence techniques, as well as some’mob-control’ tactics. They also try to make use of the new (horizontal) networks they have been building over the years. The latter give rise to small groups who do the kind of jobs that provide the opportunity to cash in on their new competencies. The range of activities that former militia members engage in is very broad. Ad hoc groups can be hired to perform a wide range of paramilitary or commando-style tasks. In a city and country where land scarcity is biting, many communities seek help to chase away so-called’allochthones’ or migrant settlers. A somewhat less delinquent form of employment is that of body guard or other security-related occupation. Since the beginning of the present conflict this sector has been growing exponentially in terms of both supply and demand. The massive supply of manpower has led to a sharp decline in wages, large-scale exploitation and other abuses which are often settled in a violent way.

Politicians are important customers in this security sector. Their needs differ widely from the clandestine intimidation of fellow politicians to guaranteeing the security of political meetings. Other activities in which ex-combatants feature are hardly distinguishable from those of the peaceful civil society: organising, promoting or simply populating demonstrations or election meetings. Sometimes it becomes even more explicit: last year militia leader’General’ Jimmy Willy founded the’Convention of the demobilised for the victory of Laurent Gbagbo’.

Although’Guantánamo’ remains an important locus of the militia’s post-conflict socialisation and reinvention, it must be situated within an even larger landscape of urban political action. As the 21st century advances, one encounters more and more examples of post-conflict areas where militias continue to interfere with public life. Some see this rising’militianisation’ as an indicator of growing brutalisation of political life in’young democracies’ such as has been seen in Liberia and Iraq.

Since the introduction of the multiparty system in 1990 Ivorian democracy has been transforming itself deeply and, like many countries around the world, even the most established democracies, it has seen the rise of populism and with it the dramatic impact of a booming mass media and new media. In Côte d’Ivoire this is consolidated by the so-called’media of proximity’: novel small-scale but pervasive formats of assembly, expression of opinion, and mobilisation. During the last ten years Abidjan has witnessed the creation of hundreds of popular parliaments. Mid-way into the present conflict the commune of Yopougon alone counted about 21 such sites which give themselves labels of democratic institutions such as’agora’,’parliament’,’senate’, or congress’ but also’Douma’ or’Black Caucus’. Their meetings attract audiences of between 25 to 1500 people who are lectured on, among other things, current political events. The inventive and often rhetorically gifted orators call themselves’political analyst’ or even’professor’. While these popular parliaments mainly voice a pro-presidential point of view, the opposition has developed a more small-scale, fragmented and covert but equally widespread format of political mobilisation called’grins’ – best translated as tea parties. Grins belong to a wider tradition of socialisation among Muslims and or Mande people throughout West Africa. There is no connection here to the way in which conservative voters are presently being mobilised in the US. But in like fashion, the Ivorian tea-parties (such as those in Burkina Faso in the run up to the 2005 elections) have been re-engineered by political entrepreneurs.

The’grins’ and popular parliaments, which more often than not advertise themselves as’spaces of free expression’ are products of the populist tactics employed by the president, his opponents, other established and emerging politicians and political entrepreneurs. This approach addresses the urban masses’from below’ with messages that in fact originate’from above’, or rather from particular locations other than the spontaneous, undisciplined voice of the people. All this is taking place outside the regular structures of political parties which in Côte d’Ivoire, like many other places around the world (not least of which are the old democracies of Europe) have lost most of their faithful followers and for the sake of a volatile electorate must constantly try to tap new, hybrid formats of popular expression and political activism.

It is in these new formats of populism where the Abidjanese former militia members can make the most of their newly acquired competencies: as agitators, for instance, using words if possible, violence if necessary; as servants of certain politicians but equally against them if necessary. At times they are involved in open public display, while at others their impact is felt through clandestine manoeuvres. In this new multi-layered and multi-centred topography of democratic action Guantánamo is both a base camp for violence-ridden political labour and a refuge against brutal misrecognition and juvenile marginalisation.

Text: Karel Arnaut (UGent – 10/11/2010)

Photographs: Raymond Dakoua///Article N° : 9869