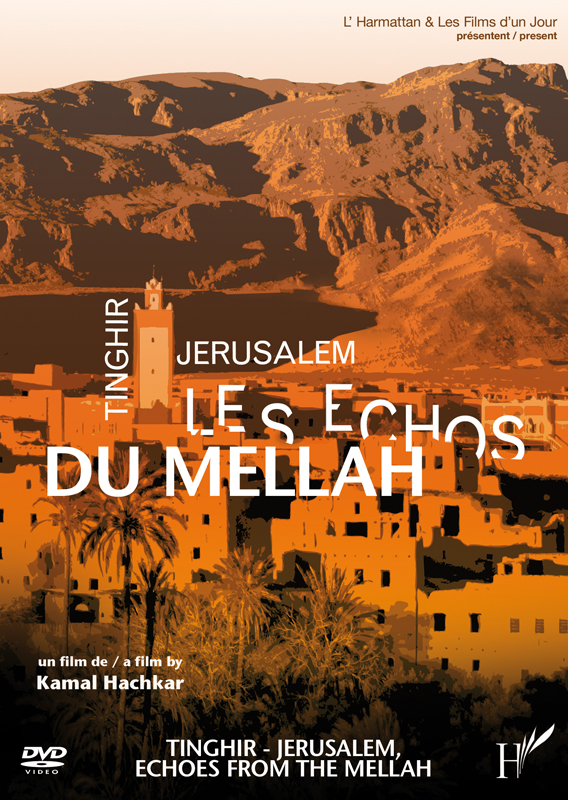

Kamal Hachkar’s documentary film Tinghir-Jerusalem: Echoes of the Mellah (2011) has become one of the most controversial films in the history of Moroccan cinema.

Since it first aired on the Moroccan public television channel 2M in April 2012, Tinghir-Jerusalem has been the subject of intense debates between the ideological bastions of extreme Arab-Islamism and the Amazigh (Berber) movement and other secular forces in the Moroccan public sphere. Between detractors and defenders, Tinghir-Jerusalem has continued to make headlines for months as it tours the country and the world. It made prominent headlines last week on the occasion of the National Film Festival in Tangier (February 1-9). Even before the opening of the most important annual event for Moroccan cinema, a few dozen Islamists and other opponents of the film gathered in the city to protest the selection of the documentary for competition at the festival. They chanted slogans against the festival organisers and the film’s’normalisation’ of relations with Israel. There are many grounds on which such a dogmatic call for censorship can be debunked, not least of which is that it cannot be responsibly defended by any film-literate person who has actually seen Tinghir-Jerusalem. Another ground is that competition at the festival is open to any Moroccan film made in the year running up to the festival.

It is obvious that Tinghir-Jerusalem has been politicised by certain parties in the Moroccan public sphere for electoral and other populist reasons. The Islamists and their ideological bedfellows protesting in Tangier were outraged by the filmmaker’s trips to Israel to interview Moroccan Jews about the trauma of their semi-voluntary aliyah to Palestine in the 1950s and 1960s. In the Islamists’ view, every Moroccan citizen should boycott Israel, including visits to the Jewish state. The same fatwa applies to Israelis: they should not be allowed to visit Morocco. The reality discredits this ideological fascism at many levels. To begin with, Morocco entertains strong trade relations and intelligence exchanges with Israel. Secondly, Moroccan citizens visit Israel every year. Thirdly, thousands upon thousands of Israelis hold Moroccan passports and visit Morocco all year round without experiencing any harassment or constraints. Last but not least, one of the guests of honour at the ruling Moroccan Islamist party’s last national congress is an Israeli citizen named Ofer Bronchtein.

The exodus of the native Jewry is one of the most ambiguous and tabooed topics for public debate in postcolonial Morocco. Due to a combination of factors – particularly, the formidable lobbying powers of the international Zionist movement, the rise of anti-Semitism under the expansion of Nasserism across North Africa and, finally, the complicity of the Moroccan regime – dozens of thousands of Jews left independent Morocco sometimes without knowing why or what was awaiting them. Historians have documented this tragedy by revealing, for example, how the Jewish population of Morocco has gone down from over 250,000 at the time of Independence in 1956 to less than 3,000 individuals today. It is only in recent years that this dark chapter of national history has gradually returned to public attention thanks in large part to Moroccan cinema. Filmmakers like Mohamed Ismail (Goodbye Mothers, 2007) and Hassan Benjelloun (Where Are You Going, Moshe? 2007) have made popular films about the mass migration of native Jews after 1956. Nabil Ayouch (My Land, 2011) and Kathy Wazana (They Were Promised the Sea, 2010) have also made remarkable documentaries on the Jewish dimension of Moroccan identity. Hachkar’s documentary is only the latest in a growing body of films on this delicate subject, which is crucial to Moroccan cinema’s contribution towards the rise of a democratic and secular nation.

The scale of the traumatic exodus for Moroccan Jews and their native country for over 2000 years is only beginning to become apparent to Moroccans. However, the parallel rise of populism in Moroccan politics in recent years, particularly after 2011, threatens this positive development. Morocco’s response to popular uprisings in the region brought the Islamists to power in November 2011. In consequence, Islamists of all shades have been emboldened by this electoral victory to censor any artistic work which is not « proper » in their eyes. The monarchy, which de facto still holds the levers of power in Morocco, has been happy to let Islamists embrace populist politics as long as they do not question its own political and economic powers. Islamists have likewise been satisfied with this deal which allows them to maintain their voting base in the face of the government’s failure to reform the political and economic Makhzen. Among the recent victims of this devil’s pact between the king and the imam is Hachkar’s Tinghir-Jerusalem, which was banned from screening in Agadir last November. Fortunately, the ban did not reoccur in Tangier last week because the embarrassment would have been too much bad publicity for both the monarchy and the Islamist ruling party because of the national festival’s international visibility.

The monarchy actually scored a handsome point against the Islamists in Tangier. Dozens of Islamist protesters, mostly supporters of the ruling Justice and Development Party (PJD), staged another protest in front of Roxy Cinema where the film was being screened to a packed audience on Tuesday 05 February. 2M TV, which is both the co-producer of the documentary and a staunch supporter of the monarchy, took the camera to the pious protesters. The result was a complete political crusade against the Islamist party. The filmed interviews, which were aired in the heavily watched evening news bulletin on the same day, revealed that most of the protesters had not actually seen the film. However, 2M TV and MAP (the official news agency) censored the film in an insidious ways. The film title had been altered overnight from Tinghir-Jerusalem to Tinghir-al-Quds.’Al-Quds’ is the Arabic name for Jerusalem and the term that Islamists uniformly favour to Jerusalem, which they say is the Zionist occupier’s name for what should be the capital of the Palestine state. The national television had obviously changed the name to crush the Islamists in their own ideological battleground. In so doing, however, both 2M TV and MAP actually distorted the message of the film because’Jerusalem’ is what the Moroccan Jews in the film call the sacred capital of their faith.

In the end, the camera scored historic points against both the king and the imam: Tinghir-Jerusalem won the festival’s Prize for First Work on Sunday 10 February. The prestigious prize crowned the film’s artistic value, historical veracity and political courage. Its Moroccan-French director is a young history teacher at a Parisian high school. Born in 1979, Hachkar was barely six months old when he left Tinghir with his family. Tinghir is a small city in the forsaken southeastern desert of Morocco. They left for France where his father was a manual labourer since 1968, the time when the last Jews also left town. It was through the family’s annual homecomings that Kamal learned from his grandfather about the erstwhile existence of Jews in Tinghir. This came both as a shock and a big discovery for the adolescent Kamal. It sparked in him an interest in history as an academic subject and an individual quest for his secular Amazigh identity with its Jewish and Muslim tributaries. The young beur in search of his cultural identity’s moorings decided to learn Arabic and Hebrew to better decipher the human mystery behind the still standing cemetery, ghost houses and resold shops of Tinghir’s Jews. He spent years doing research in the archives and meeting the survivals of the Aliyah from his hometown, particularly in Israel. Years later and with academic knowledge and Hebrew mastered, the now teacher of history decided to make a film about a hidden chapter of Morocco’s contemporary history. The documentary is as much about Hachkar as about the Jews of his hometown.

Tinghir-Jerusalem opens with him returning to Tinghir to make the film. The documentary’s first part consists of the recollections of old folk in the town about their Jewish neighbours, childhood playmates and adulthood friends, who now live in Israel and still speak Tamazight (Berber) with astounding fluency. His main guide in the ruins of Tinghir’s mellah (Jewish quarter) and marketplace is his own grandfather, who unfortunately passed away last Sunday at the age of 81 (just hours before the film won the festival prize in Tangier). The second part of Tinghir-Jerusalem takes us to Israel to meet the hitherto invisible Jews of Tinghir. Their recollections of their Moroccan homeland and strong attachment to it are touching. They are happy to meet Hachkar and ask him about friends and neighbours. Some old women chant Amazigh songs in the film. Their offspring are well informed about their Moroccan past and long to visit the country of their parents.

The film documents the still unexplored life of Amazigh Jews (unlike the relative abundance of scholarship by and on urban Jews). Also unlike affluent Jewish families from Moroccan cities, the Jews of Tinghir like most Amazigh Jews were poor and could not stay behind or move to Europe or North America like thousands of their richer compatriots. Upon their arrival in the promised land, the Jews of Tinghir were condemned to relative poverty and danger in the border settlements. Their traditional craftsmanship and trade acumen were of little help in a modernising country like Israel.

In the end, Tinghir-Jerusalem is a riveting documentary which promises more debates and films on the place of Jews and Imazighen (Berbers) in Morocco today. The real battle camouflaging in the controversy about the film is one pitting secular forces against the Islamists and their ideological partners, the Pan-Arabists, who have yet to accept the recent constitutional recognition of the Amazigh and Jewish identities of Morocco. Heavily repressed until recently, the Islamists are taking on the character of the police regime they are supposed to bring to an end. There is a real threat today to secular values and religious diversity from the ruling Islamists in Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt, who have censored free speech on multiple occasions since coming to power. In Morocco, cinema’s increasing audacity and production volume make it one of the main battlegrounds for current and coming culture wars. However, their positive contribution to the country’s democratic evolution requires a more solid framework for the protection of freedom of expression against the culture of censorship and ideological decadence. There is a Jew in every Moroccan and all censorship of the country’s plural identity will only lead to more lost decades and perhaps civil strife in a country with a long record of peaceful cohesion and hospitality to others.

///Article N° : 11305